Bird Flu in Cattle (Part 2) - Strong Evidence the Alleged Infection is a Technical Falsehood

New preprint published

In part 2 of this series, I delve deeper into the concerns raised in part 1. A new preprint on this that I submitted yesterday was just accepted at OSFPreprints. Here is the abstract:

The recent reports of bird flu infection in cattle in the U.S. have triggered concerns that (unpasteurized) milk or meat from affected animals could be unsafe for consumption and raised fear the virus could further evolve, spill over to humans, and cause another major pandemic with an expected fatality much higher than for COVID-19. The identification of the viral infection in cattle, based on PCR testing of mild or asymptomatic cases, raises similar questions as during the COVID-19 pandemic. Meanwhile, the USDA has publicized the genetic information of the bird flu virus, apparently isolated from numerous hosts including birds, cattle, and other mammals.

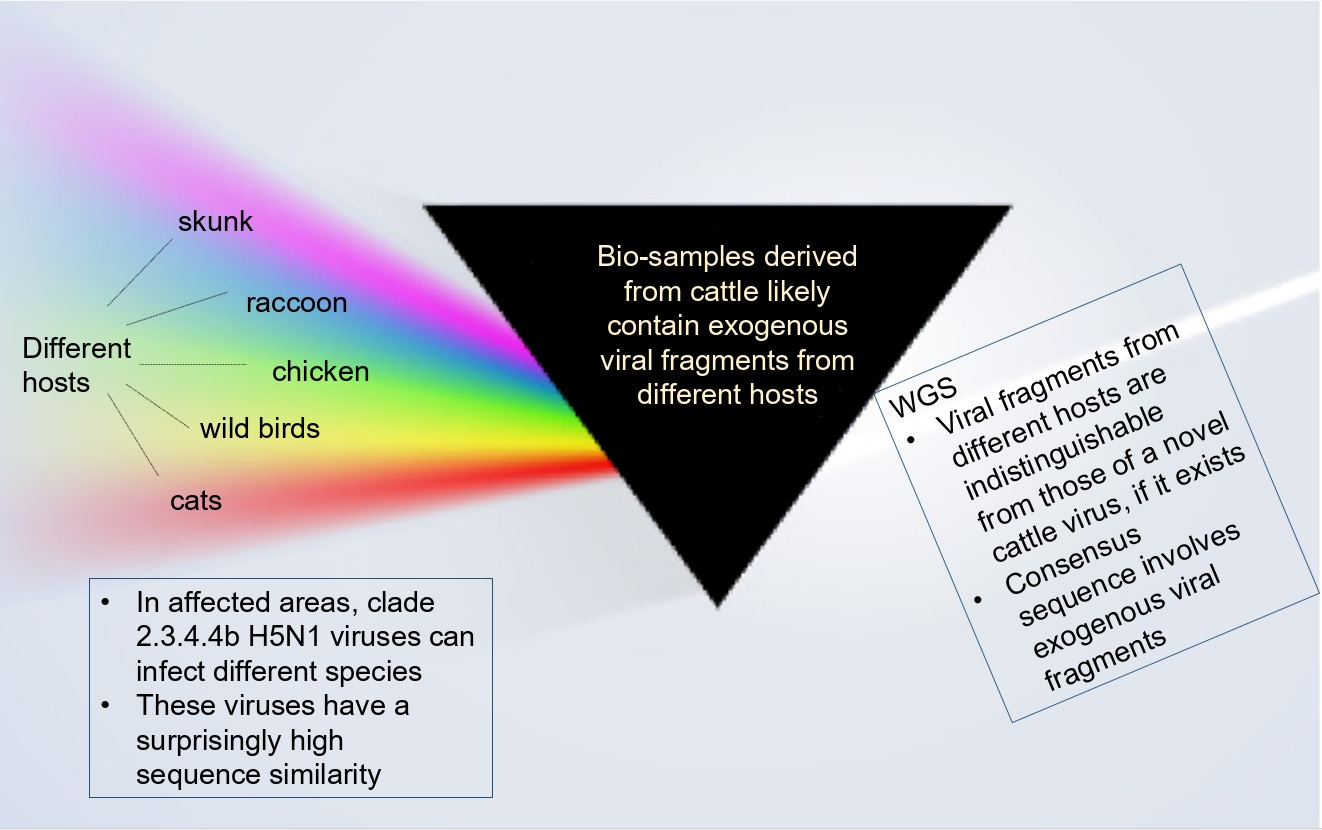

This article gives an independent analysis of what is meant by “positive cases” and the “confirmed” presence of the virus. Specifically, a closer inspection of the genetic analysis reveals several gaps similar to those only recently discovered involving whole-genome sequencing protocols that remain largely unaccounted. The infection in cattle poses an additional challenge via environmentally derived viral genome fragments that these animals are constantly exposed to. The issue of contamination via off-target gene fragments during whole-genome sequencing has previously been widely under-appreciated, even in much simpler contexts such as the sequencing of bacterial isolates. The type of contamination in the context of H5N1 and cattle is more complex and does not seem to ever have been considered before and appears technically challenging to resolve, if at all possible.

Combined with several other considerations, this gives strong evidence the presumed confirmed positive cases are simply the result of some technological errors. The publicly available genomic data from WGS are likely severely biased and will, therefore, adversely affect any downstream analyses. The article closes with recommendations to help regain public trust in public health agencies and their recommendations.

In essence, I have not been able to find any convincing argument that demonstrates the cattle are infected with a live virus. To date, the alleged presence of the virus in cows, none of which have any specific symptoms, are essentially based on (1) PCR routines with Ct values in their 30s (up to 40, samples are considered positive), and (2) genetic information.

In the preprint, I argue that there are likely substantial errors in the genetic routines. This is based on the following observation.

Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) has greatly enhanced our understanding of complex biological phenomena and has increasingly been utilized for the clinical diagnosis and surveillance of pathogens. However, only in 2020, did Goig et al. [8] observe that the potential role of contamination is seldom considered.

Here, contaminated sequences are understood as those containing large genomic regions from non-target organisms.

Specifically analyzing more than 4000 bacterial samples from 20 different studies using a taxonomic filter, they found that shockingly:

Contamination events are unexpectedly frequent across bacterial WGS studies and can introduce large biases in variant analysis.

Examples of contamination included samples with more than 10% of reads from non-target organisms, and in one case, it was even 40%. Contaminants in WGS can constitute virtually all reads in some samples.

There is a false assumption that microbiological cultures are mostly free of non-target organisms. In addition, residual contaminants not believed to map to the reference genomes or are thought to be removed using standard filter cutoffs.

Most bacterial WGS analysis pipelines lack specific steps aimed at dealing with contaminant data. Using standard mapping quality parameters turned out insufficient to remove non-target reads in the sequencing file.

In the article, I provide arguments as to why the situation with bird flu in cattle leads to analogous, and even more complex issues that would be difficult to re-mediate, if at all possible (summarized in the Figure below).

(Source: https://osf.io/preprints/osf/nkc5v)

For more details, please see the preprint.

As there is an increased push for countermeasures, such as protective gear for farmers and vaccines (humans and cattle, and possibly other species?!), it does all remind me too much of what we just went through.

The situation in the cattle is in many regards even more involved than what we had experienced at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Aspects such as environmental genetic contaminants and the questionable sickness (rather its absence) in those animals make it harder to demonstrate what is really going on (to date, none of the cows has shown any clinical symptoms that could not be attributable to other factors, especially in the context of BigAg). At the same time, they add additional complexities and confounders to testing (aka, the identification of the pathogen). While I cannot prove there is no H5N1 virus in those cattle, the technical problems I described in the preprint do not seem to have been acknowledged before.

In sum, rather than finding a viable virus, the tests have only identified viral fragments. Due to the unaccounted contamination issue in the form of exogenous genetic material of closely related species, the outcome of whole-genome sequencing is impaired and likely false.

Cattle exposed to open water sources frequented by migratory waterfowl are likely to ingest water contaminated with H5N1 virus and genomic nucleic acid. Which will yield false positives. Note lack of USDA documentation of either cattle to cattle transmission or human to human transmission. At this point i have seen no H5N1 epidemic evidence in any non avian species.

congratulations Siguna on the preprint